PRINT AS PDF

Seemingly, every century produces only a handful of towering diplomats who leave an indelible mark on history. The complicated Henry Kissinger, who passed away last week at age 100, was one such diplomat.

As entire books have been written on his life and legacy, brilliance and controversy, leadership and personality, there is little need for yet another biographical sketch. Moreover, as many opinions have hardened to unyielding rigidity, a fresh biographic portrait would only exacerbate divisions.

Instead, what is more useful is to briefly examine why Secretary Kissinger had a giant impact on the world’s geopolitical evolution and to provide an example. His impact on history will continue to provide ample research opportunities for graduate students, PhD’s, academics, and journalists for decades to come.

In leadership, success often arises at the intersection of circumstance and choice. Often, circumstances are beyond the control of the actors—both leaders and states—who can only seek to adapt to the requirements of those circumstances. At the same time, choices can lead to a cascade of outcomes across the fabric of time, leading to new structures and rules that define the world order that emerges and engagement within that order.

Henry Kissinger possessed a deep understanding of history, knowledge of history’s great diplomats, and insight into the structural dynamics that shape the world. He had the capacity to recognize the opportunities that could be uncovered by that knowledge, understanding, and insight. He had the ability to make choices to harness those opportunities. Those attributes empowered him to play a pivotal role in helping the United States build a relationship with China. In turn, that relationship undermined the Soviet Union’s geopolitical influence and capacity to exert power.

When Kissinger joined the Nixon Administration in 1969, the United States was confronted by a stiffening Soviet challenge brought about by nuclear parity, a raging conflict in Indochina, a weakening NATO alliance, and an increasingly assertive Non-Aligned World. The doctrine of Containment that had anchored post-World War II policy since the Truman Administration was fraying. Recurrent crises increasingly defined world affairs.

Early on, Kissinger recognized the impact a deepening interconnectedness, rapid transmission of information, and participation of a growing number of states was having on world affairs. These dynamics were transforming once local or regional matters into global ones. Politics had become global. In a 1969 essay, he explained:

For the first time, foreign policy has become global. In the past, the various continents conducted their foreign policy essentially in isolation. Throughout much of history, the foreign policy of Europe was scarcely affected by events in Asia. When, in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the European powers were extending their influence throughout the world, the effective decisions continued to be made in only a few great European capitals. Today, statesmen face the unprecedented problem of formulating policy for well over a hundred countries. Every nation, no matter how insignificant, participates in international affairs. Ideas are transmitted almost instantaneously. What used to be considered domestic events can now have world-wide consequences.

Kissinger went on to argue for a “burst of creativity… not so much for the sake of other countries as for our own people, especially the youth.” That meant daring to consider ideas that fell outside the familiar, long-established contours of American foreign policy thinking. It meant probing for openings to recast the long-running Cold War in which the United States and free world were locked in an ideological, political, and economic battle against the Communist bloc.

Kissinger saw just such an opportunity in China. The Soviet Union, accustomed to playing the lead role in the Communist world sought to maintain that dominance at China’s expense. Tensions escalated to the point that there had been seven months of border skirmishes between the two Communist powers in 1969.

During that time, the Soviet Union put out feelers to solicit possible American support or, at least understanding, for a possible more assertive approach. Exploring those feelers provided a tempting opening that could lead to a possible thaw in bilateral United States-Soviet relations. At the best, it could even lead to a dramatic softening of the Cold War rivalry.

Instead, Kissinger advised that the United States should make clear to the Soviet leadership that it would not accommodate a more aggressive Soviet policy toward China. In a September 29, 1969 memo to President Nixon, Kissinger wrote:

The principal gain in making our position clear would be in our stance with respect to China. The benefits would be long rather than short-term, but they may be none the less real. Behavior of Chinese Communist diplomats in recent months strongly suggests the existence of a body of opinion, presently submerged by Mao’s doctrinal views, which might wish to put US/Chinese relations on a more rational and less ideological basis than has been true for the past two decades.

Kissinger had peered beyond the short-term. In doing so, he had glimpsed the larger picture in the swirling currents of history. He saw emergent hints that the United States-China rupture need not remain the permanent aspect of world affairs as was the prevailing foreign policy assumption. He perceived that an opportunity for rapprochement could emerge. He conceived the benefits of a future where the United States and China were closer to one another than either was to the Soviet Union.

A creative diplomatic approach coupled with passing up short-term considerations for long-term returns could give birth to that future world. Less than two years later, Kissinger made a secret trip to China that paved the way for President Nixon’s landmark February 1972 trip. That sequence of events helped tilt the Cold War balance of power toward the U.S. and its allies.

Kissinger’s role in this undertaking is among his greatest acts of statesmanship. It was arguably riskier to wait to see if there could be an opening to China with its lack of a guaranteed positive outcome than it would have been to pursue a potentially immediate improved relationship with the Soviet Union.

Risk-averse analysts would almost have certainly advised accommodating the Soviet Union based on the near-term costs-benefits calculus. Numerous Cold War-weary political leaders would have leaped at the opportunity for de-escalation with the USSR that had suddenly materialized.

Kissinger chose otherwise. He took a large risk based on his understanding of the long-term benefits that could be unlocked from a restoration of U.S.-China relations. He saw the consequential historic stakes that were involved and how his preferred choice could contribute to a more peaceful world in the longer-term if his assessment were correct.

In his seminal work, Diplomacy, Kissinger explained, “The statesman is permitted only one guess; his mistakes are irretrievable… The statesman must act on assessments that cannot be proved at the time that he is making them; he will be judged by history on the basis of how wisely he managed the inevitable change and, above all, by how well he preserves the peace.”

In the 21st Century, China has become the single nation that could pose a credible challenge to the United States. Although relations have eroded, especially since 2017, the relationship has not ceased to exist. There remains a foundation for a renewed relationship. Without the 1972 opening to China, such a foundation might not exist today. Moreover, the world would be a very different place. Perhaps then, the Soviet Union might have gone on to subdue China. Afterward, an ascendant Soviet Union might have triumphed in the Cold War with stark consequences for the world’s free peoples.

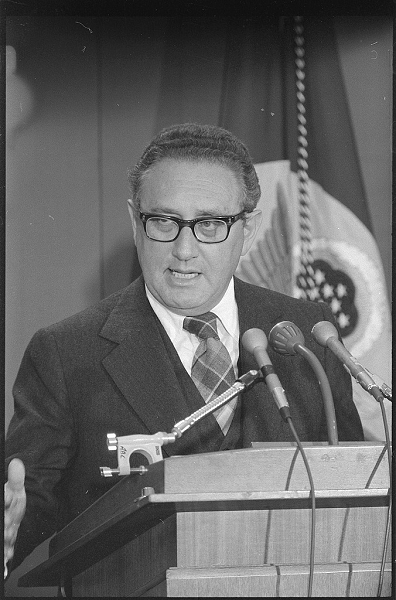

Henry Kissinger at a press conference, November 10 1975 (Source: U.S. Library of Congress)