PRINT AS PDF

Yesterday, President Obama visited Lehman College, engaged in a round-table discussion with a number of students aimed at exploring opportunities to help them succeed, and launched a new non-profit initiative aimed at empowering Minority youth. Following his roundtable discussion, the President made brief remarks in which he noted the importance of listening to the people one is seeking to help. He explained, “[I]f we’re going to be successful in addressing some of the challenges that young men of color face around the country, that their voices have to be part of how we design programs and how we address these issues. “

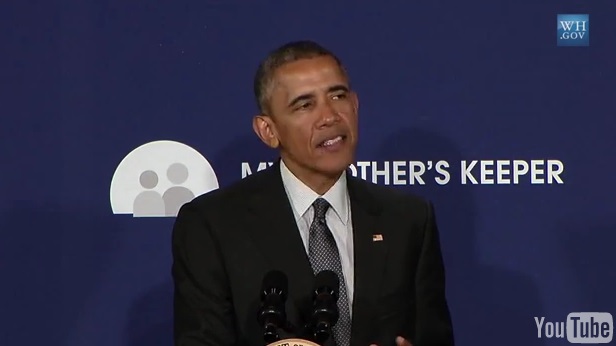

Afterward, the President made a speech before a larger audience in which he formally announced the “My Brother’s Keeper Alliance” initiative. In that address, he invoked the United States’ longstanding reputation as a land of opportunity for all, declaring, “[W]e believe in the idea that no matter who you are, no matter what you look like, no matter where you came from, no matter what your circumstances were, if you work hard, if you take responsibility, then America is a place where you can make something of your lives.”

The transcript of the President’s speech is below.

Remarks by the President at Launch of the My Brother’s Keeper Alliance

Lehman College

West Bronx, New York

2:56 P.M. EDT

THE PRESIDENT: Hello, New York! Give Darinel a big round of applause for that introduction. Thank you so much. Thank you. Everybody, please have a seat. We are so proud of Darinel. We want to thank him for being such a great role model for other students here in New York and around the country.

I want to give a shout-out to a friend of mine who happens to be your Assemblyman — Michael Blake. Where’s Michael? He is around here somewhere. There he is. You got to stand up, Michael. We’re still teaching him about politics. When the President introduces you, you got to stand up. Get some TV time.

So Mike grew up in tough circumstances, as well. He worked hard, went to a good college. He joined my campaign, worked in the White House. Now he’s in public office to make sure that other young people like him have every chance in the world. So we couldn’t be prouder of him. It’s great to see.

So I’m getting practice for Malia and Sasha leaving home. I’ve got all these incredible young people who worked on the White House staff who are now doing all kinds of great things.

I want to thank all the members of Congress and elected officials who are in the house. You’ve got a couple of proud Lehman graduates — Eliot Engel — where’s Eliot? There he is. And Jose Serrano. And we’ve got some more folks — we’ve got three other folks from the New York delegation — Gregory Meeks — — the always dapper Charlie Rangel — — the outstanding Yvette Clarke. And visiting from Florida — Frederica Wilson. But they all share the same passion that I do, and that is making sure every young person in this country has opportunity.

That’s why we’re all here today. Because we believe in the idea that no matter who you are, no matter what you look like, no matter where you came from, no matter what your circumstances were, if you work hard, if you take responsibility, then America is a place where you can make something of your lives.

And I want to thank Lehman for hosting us here today. And our community college system — the CUNY system — our public education institutions, they are all pathways for success. And we’re very proud of what they do.

Everything that we’ve done since I’ve been President, the past six and a half years — from rescuing the economy to giving more Americans access to affordable health care, to reforming our schools for all of our kids — it’s been in pursuit of that one goal: creating opportunity for everybody. We can’t guarantee everybody’s success. But we do strive to guarantee an equal shot for everybody who’s willing to work for it.

But what we’ve also understood for too long is that some communities have consistently had the odds stacked against them; that there’s a tragic history in this country that has made it tougher for some. And folks living in those communities, and especially young people living in those communities, could use some help to change those odds.

It’s true of some rural communities where there’s chronic poverty. It’s true of some manufacturing communities that have suffered after factories they depended on closed their doors. It’s true for young people of color, especially boys and young men.

You all know the numbers. By almost every measure, the life chances of the average young man of color is worse than his peers. Those opportunity gaps begin early — often at birth — and they compound over time, becoming harder and harder to bridge, making too many young men and women feel like no matter how hard they try, they may never achieve their dreams.

And that sense of unfairness and of powerlessness, of people not hearing their voices, that’s helped fuel some of the protests that we’ve seen in places like Baltimore, and Ferguson, and right here in New York. The catalyst of those protests were the tragic deaths of young men and a feeling that law is not always applied evenly in this country. In too many places in this country, black boys and black men, Latino boys, Latino men, they experience being treated differently by law enforcement — in stops and in arrests, and in charges and incarcerations. The statistics are clear, up and down the criminal justice system; there’s no dispute.

That’s why one of the many things we did to address these issues was to put together a task force on community policing. And this task force was made up of law enforcement and of community activists, including some who had led protests in Ferguson, some who had led protests here in New York — young people whose voices needed to be heard. And what was remarkable was law enforcement and police chiefs and sheriffs and county officials working with these young people, they came up with concrete proposals that, if implemented, would rebuild trust and help law enforcement officers do their jobs even better, and keep them and their communities even safer.

And what was clear from this task force was the recognition that the overwhelming majority of police officers are good and honest and fair, and care deeply about their communities. And they put their lives on the line every day to keep us safe. And their loved ones wait and worry until they come through that door at the end of their shift.

As many of you know, New York’s finest lost one of its own today — Officer Brian Moore, who was shot in the line of duty on Saturday night, passed away earlier today. He came from a family of police officers. And the family of fellow officers he joined in the NYPD and across the country deserve our gratitude and our prayers not just today but every day. They’ve got a tough job.

Which is why, in addressing the issues in Baltimore or Ferguson or New York, the point I made was that if we’re just looking at policing, we’re looking at it too narrowly. If we ask the police to simply contain and control problems that we ourselves have been unwilling to invest and solve, that’s not fair to the communities, it’s not fair to the police. What we gathered here to talk about today is something that goes deeper than policing. It speaks to who we are as a nation, and what we’re willing to do to make sure that equality of opportunity is not an empty word.

Across the country and in parts of New York, in parts of New Jersey, in parts of my hometown in Chicago, there are communities that don’t have enough jobs, don’t have enough investment, don’t have enough opportunity. You’ve got communities with 30, or 40, or 50 percent unemployment. They’ve been struggling long before the economic crisis in 2007, 2008. Communities without enough role models. Communities where too many men who could otherwise be leaders, who could provide guidance for young people, who could be good fathers and good neighbors and good fellow citizens, are languishing in prison over minor, nonviolent drug offenses.

Now, there’s no shortage of people telling you who and what is to blame for the plight of these communities. But I’m not interested in blame. I’m interested in responsibility and I’m interested in results.

That’s why we’ve partnered with cities to get more kids access to quality early childhood education — no matter who they are or where they’re born. It’s why we’ve partnered with cities to create Promise Zones, to give a booster shot to opportunity. That’s why we’ve invested in ideas from support for new moms to summer jobs for young people, to helping more young people afford a college education.

And that’s why, over a year ago, we launched something we call My Brother’s Keeper — an initiative to address those persistent opportunity gaps and ensure that all of our young people, but particularly young men of color, have a chance to go as far as their dreams will take them. It’s an idea that we pursued in the wake of Trayvon Martin’s death because we wanted the message sent from the White House in a sustained way that his life mattered, that the lives of the young men who are here today matter, that we care about your future — not just sometimes, but all the time.

In every community in America, there are young people with incredible drive and talent, and they just don’t have the same kinds of chances that somebody like me had. They’re just as talented as me, just as smart. They don’t get a chance. And because everyone has a part to play in this process, we brought everybody together. We brought business leaders and faith leaders, mayors, philanthropists, educators, entrepreneurs, athletes, musicians, actors — all united around the simple idea of giving all our young people the tools they need to achieve their full potential.

And we were determined not to just do a feel-good exercise, to write a report that nobody would read, to do some announcement, and then once the TV cameras had gone away and there weren’t protests or riots, then somehow we went back to business as usual. We wanted something sustained. And for more than a year, we’ve been working with experts to identify some of the key milestones that matter most in every young person’s life — from whether they enter school ready to learn, to whether they graduate ready for a career. Are they getting suspended in school? Can we intervene there? Are they in danger of falling into the criminal justice system? Can we catch them before they do? Key indicators that we know will make a difference. If a child is reading by the third grade at grade level, we know they’ve got a chance of doing better. If they aren’t involved with the criminal justice system and aren’t suspended while they’re in school, we know they’ve got a chance of doing better. So there are certain things that we knew would make a difference.

And we’ve looked at which programs and policies actually work in intervening at those key periods. Early childhood education works. Job apprenticeship programs work. Certain mentoring programs work. And we’ve identified which strategies make a difference in the lives of young people, like mentoring, or violence prevention and intervention.

And because we knew this couldn’t be the work of just the federal government, we challenged every community in the country — big cities, small towns, rural counties, tribal nations — to publicly commit to implementing strategies to help all young people succeed. And as a result, we’ve already got more than 200 communities across the country who are focused on this issue. They’re on board and they’re doing great work. They’re sharing best practices. They’re sharing ideas.

All of this has happened just in the last year. And the response we’ve gotten in such a short amount of time, the enthusiasm and the passion we’ve seen from folks all around the country proves how much people care about this. Sometimes politics may be cynical, the debate in Washington may be cynical, but when you get on the ground, and you talk to folks, folks care about this. They know that how well we do as a nation depends on whether our young people are succeeding. That’s our future workforce.

They know that if you’ve got African American or Latino men here in New York who, instead of going to jail, are going to college, those are going to be taxpayers. They’re going to help build our communities. They will make our communities safer. They aren’t part of the problem, they’re potentially part of the solution — if we treat them as such.

So we’ve made enormous progress over the last year. But today, after months of great work on the part of a whole lot of people, we’re taking another step forward, with people from the private sector coming together in a big way. We’re here for the launch of the My Brother’s Keeper Alliance, which is a new nonprofit organization of private sector organizations and companies that have committed themselves to continue the work of opening doors for young people — all our young people — long after I’ve left office. It’s a big deal.

I want to thank the former CEO of Deloitte, Joe Echevarria, who’s been involved for a long time. He has taken the lead on this alliance. Joe, stand up. You’ve done an incredible job. Just like the My Brother’s Keeper overall effort that we launched last year, Joe and My Brother’s Keeper Alliance — they’re all about getting results. They’ve set clear goals to hold themselves accountable for getting those results: Doubling the percentage of boys and young men of color who read at grade level by the third grade. Increasing their high school graduation rates by 20 percent. Getting 50,000 more of those young men into post-secondary education or training.

They’ve already announced $80 million in commitments to make this happen, and that is just the beginning. And they’ve got a great team of young people who helped to work on this, a lot of them from Deloitte. We appreciate them so much. We’re very proud of the great work that they did.

But here’s what the business leaders who are here today — and Joe certainly subscribes to this — will tell you, they’re not doing this out of charity. The organizations that are represented here, ranging — as varied as from Sprint to BET — they’re not doing it just to assuage society’s guilt. They’re doing this because they know that making sure all of our young people have the opportunity to succeed is an economic imperative.

These young men, all our youth, are part of our workforce. If we don’t make sure that our young people are safe and healthy and educated, and prepared for the jobs of tomorrow, our businesses won’t have the workers they need to compete in the 21st century global economy. Our society will lose in terms of productivity and potential. America won’t be operating at full capacity. And that hurts all of us.

So they know that there’s an economic rationale for making this investment. But, frankly, this is also about more than just economics; it’s about values. It’s about who we are as a people.

Joe grew up about a mile from here, in the Bronx. And as he and I were sitting there, listening to some incredible young men in a roundtable discussion, many of them from this community, their stories were our stories. So, for Joe and I, this is personal, because in these young men we see ourselves.

The stakes are clear. And these stakes are high: At the end of the day, what kind of society do we want to have? What kind of country do we want to be? It’s not enough to celebrate the ideals that we’re built on — liberty for all, and justice for all and equality for all. Those can’t just be words on paper. The work of every generation is to make those ideals mean something concrete in the lives of our children — all of our children.

And we won’t get there as long as kids in Baltimore or Ferguson or New York or Appalachia or the Mississippi Delta or the Pine Ridge Reservation believe that their lives are somehow worth less.

We won’t get there when we have impoverished communities that have been stripped away of opportunity, and where, in the richest nation on Earth, children are born into abject poverty.

We won’t be living up to our ideals when their parents are struggling with substance abuse, or are in prison, or unemployed, and when fathers are absent, and schools are substandard, and jobs are scarce and drugs are plentiful. We won’t get there when there are communities where a young man is less likely to end up in college than jail, or dead — and feels like his country expects nothing else of him.

America’s future depends on us caring about this. If we don’t, then we will just keep on going through the same cycles of periodic conflict. When we ask police to go into communities where there’s no hope, eventually something happens because of the tensions between societies and these communities — and the police are just on the front lines of that.

And people tweet outrage. And the TV cameras come. And they focus more on somebody setting fire to something or turning over a car than the peaceful protests and the thoughtful discussions that are taking place. And then some will argue, well, all these social programs don’t make a difference. And we cast blame. And politicians talk about poverty and inequality, and then gut policies that help alleviate poverty or reverse inequality.

And then we wait for the next outbreak or problem to flare up. And we go through the same pattern all over again. So that, in effect, we do nothing.

There are consequences to inaction. There are consequences to indifference. And they reverberate far beyond the walls of the projects, or the borders of the barrio, or the roads of the reservation. They sap us of our strength as a nation. It means we’re not as good as we could be. And over time, it wears us out. Over time, it weakens our nation as a whole.

The good news is, it doesn’t have to be this way. We can have the courage to change. We can make a difference. We can remember that these kids are our kids. “For these are all our children,” James Baldwin once wrote. “We will all profit by, or pay for, whatever they become.”

And that’s what My Brother’s Keeper is about, that’s what this alliance is about. And we are in this for the long haul. We’re going to keep doing our work at the White House on these issues. Sometimes it won’t be a lot of fanfare. I notice we don’t always get a lot of reporting on this issue when there’s not a crisis in some neighborhood. But we’re just going to keep on plugging away. And this will remain a mission for me and for Michelle not just for the rest of my presidency, but for the rest of my life.

And the reason is simple. Like I said before — I know it’s true for Joe; it’s true for John Legend, who was part of our roundtable; it’s true for Alonzo Mourning who is here, part of our board — we see ourselves in these young men.

I grew up without a dad. I grew up lost sometimes and adrift, not having a sense of a clear path. And the only difference between me and a lot of other young men in this neighborhood and all across the country is that I grew up in an environment that was a little more forgiving. And at some critical points, I had some people who cared enough about me to give me a second chance, or a third chance, or give me a little guidance when I needed it, or to open up a door that might otherwise been closed. I was lucky.

Alex Santos is lucky, too. Where’s Alex? Alex is here. Stand up, Alex. So Alex was born in Puerto Rico, grew up in Brooklyn and the Bronx, in some tough neighborhoods. When he was 11, he saw his mom’s best friend, a man he respected and looked up to, shot and killed. His older brothers dropped out of school, got caught up in drugs and violence. So Alex didn’t see a whole lot of options for himself, couldn’t envision a path to a better future. He then dropped out of school.

But then his mom went back to school and got her GED. She set an example. That inspired Alex to go back and get his GED. Actually, it’s more like she stayed on him until he went back. And I know, because just like I was lucky, I also had a mom who used to get on my case about my studies. So I could relate. But this is what Alex says about his mom: “She made me realize that no matter what, there’s a second chance in life.”

So, today, Alex is getting his GED. He’s developed a passion for sports. His dream is to one day work with kids as a coach and set an example for them. He says he never thought he could go to college; now he believes he can. All Alex wants to be is a good role model for his younger brothers, Carlos and John, who are bright and hardworking and doing well in school. And he says, “They matter so much to my life, and I matter to theirs.”

So, Alex, and his brothers, and all the young people here, all the young ones who are out there struggling — the simple point to make is: You matter. You matter to us.

It was interesting during the roundtable, we asked these young men — incredible gifted young men, like Darinel — asked them, what advice would you give us? And they talked about mentor programs and they talked about counseling programs and guidance programs in schools. But one young man — Malachi — he just talked about, we should talk about love. Because Malachi and I shared the fact that our dad wasn’t around, and that sometimes we wondered why he wasn’t around and what had happened.

But really that’s what this comes down to is, do we love these kids? See if we feel like because they don’t look like us, or they don’t talk like us, or they don’t live in the same neighborhood as us that they’re different, that they can’t learn, or they don’t deserve better, or it’s okay if their schools are rundown, or it’s okay if the police are given a mission just to contain them rather than to encourage them, then it’s not surprising that we’re going to lose a lot of them.

But that’s not the kind of country I want to live in. That’s not what America is about. So my message to Alex and Malachi and Darinel, and to all the young men out there and young boys who aren’t in this room, haven’t yet gotten that helping hand, haven’t yet gotten that guidance — I want you to know you matter. You matter to us. You matter to each other. There’s nothing, not a single thing, that’s more important to the future of America than whether or not you and young people all across this country can achieve their dreams.

And we are one people, and we need each other. We should love every single one of our kids. And then we should show that love — not just give lip-service to it, not just talk about it in church and then ignore it, not just have a seminar about it and not deliver.

It’s hard. We’ve got an accumulation of not just decades but, in some cases, centuries of trauma that we’re having to overcome. But if Alex is able to overcome what he’s been through, then we as a society should be able to overcome what we’ve been through. If Alex can put the past behind him and look towards the future, we should be able to do the same.

I’m going to keep on fighting, and everybody here is going to keep on fighting to make sure that all of our kids have the opportunity to make of their lives what they will. Today is just the beginning. We’re going to keep at this for you, the young people of America, for your generation and for all the generations to come.

So, thank you. God bless you. God bless all of you. God bless America.

END

3:27 P.M. EDT