PRINT AS PDF

In the run-up to the 2016 Presidential election and afterward, hostility toward news organizations and reporters has intensified in the United States. President Trump, some of his staff, and numerous supporters, are currently engaged in an unrelenting campaign to discredit the news media. The President has repeatedly used his Twitter account to bludgeon the news media in an attempt to rebrand the news organizations and journalists as “fake,” “fraudulent,” or “dishonest.”

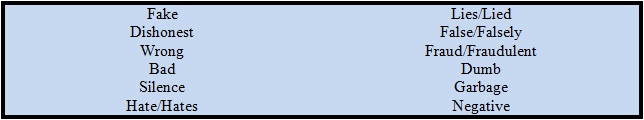

President Trump’s most commonly tweeted descriptions of the media (January 1-July 9, 2017):

Since January 1, the President has targeted CNN more than any other news outlet. The New York Times has been his most frequently targeted newspaper.

The White House has also occasionally barred select news organizations and cameras from press events. Just ahead of the July 4 Independence Day holiday, the President tweeted a violent meme directed against CNN to his more than 33 million Twitter followers.

In a nation where reverence for a free press dates back to the earliest English settlement at Jamestown in 1607, intolerance toward the news media has been mounting. On account of this increasingly harsh climate, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) announced that it has partnered with the Freedom of the Press Foundation to launch the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker. That project seeks to document “every major press freedom incident” that takes place in the United States. The U.S. Press Freedom Tracker will debut in coming weeks.

That such incidents will be documented in the United States is a fairly novel, if not disturbing, experience in American history. Recognition of the importance of a free press goes back to the nation’s origins. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the understanding that “liberty of the press” served as among the most critical safeguards for a free society, was widespread in English and American political thought. In the early days following the American Revolution, a free press was credited with having made the Revolution possible. For example, in a February 18, 1789 letter addressed to John Adams, William Cushing, who went on to serve as an Associate Justice on the U.S. Supreme Court for more than 20 years, wrote:

The propagating literature & knowledge by printing or otherwise, tends to illuminate men’s minds, & to establish them in principles of liberty… Without this liberty of the press, could we have supported our liberties against British administration? Or could our revolution have taken place? Pretty certain, it could not at the time it did.

Adams concurred. In his reply to Cushing, Adams declared, “If the press is to be stopped, and the people kept in ignorance, we [had] much better have the first Magistrate [President] and Senators hereditary.” In other words, the American Revolution would have been pointless. Limited access to relevant and reliable information would render it impossible for the public to sustain elected self-government.

In his famous defense of Thomas Paine in 1792, Thomas Erskine argued that precisely because a free press safeguards liberty, illiberal rulers reject it. He informed the court, “Of all the attainments of a people, the liberty of the press has been uniformly the last—Uniformly despotism has resisted the propagation of truth. All other concessions power has been willing to make, but against the truths of reason—against the light of knowledge, it has maintained an eternal war.”

But that was then. What about now? What about the possibility of an imperfect press? These aren’t hypothetical considerations. After all, “yellow journalism,” in which sensationalism took precedence over accuracy, offers one example of news media failure. Despite that historic experience and those questions, the verdict in favor of a free press does not change.

John Jay, who went on to become the first Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, shot down the notion that inaccurate or even ‘slanderous’ reporting justified curbing freedom of the press. Instead, in a May 5, 1786 letter to Thomas Jefferson, Jay expressed confidence that any issues presented by inaccurate reporting would be temporary. He explained, “The liberty of the press is certainly too important to the public, to be restrained for the sake of personal considerations; especially as it is in every man’s power to frustrate calumny, by not deserving censure; for altho slander may prevail for a while, yet truth and consistent rectitude will ultimately enjoy their rights.”

Jay’s words ring as true today as they did 231 years ago. Even as the latest arguments for curbing the press’ freedom are being advanced in a 21st century context—one in which the media has expanded from newspapers into radio, television, and various electronic platforms—the press’ importance to the public remains undiminished. Therefore, today’s loud rationalizations are insufficient to reverse Jay’s verdict. A free press ought to be preserved, in spite of all journalistic or editorial flaws that might manifest themselves.

Why is the issue of a creeping infringement on the nation’s press discussed in this blog? It is examined, because freedom of the press has much in common with academic freedom on which higher education depends to fulfill its mission of building humanity’s intellectual capital. Both freedoms concern the unfettered dissemination of fact and expression of opinion. The integrity of both freedoms is essential to the pursuit of the truth, creation of knowledge, and cultivation of an informed public.

Therefore, those in academe cannot be indifferent to the ongoing efforts to intimidate, discredit, and otherwise undermine the nation’s press. After all, if the dissemination of information and opinion can be stifled in one place, then it can be stifled everywhere. Once that happens, all of the precious freedoms Americans and other free peoples take for granted would be imperiled. Then, the existence of those rights would depend on nothing more than the good faith of the state, and could not count on such good faith in a state that had already suffocated a free press. Such a development would invite national stagnation or worse.

Informed public opinion is the antidote for that outcome. In his 1975, Nobel Peace Prize Lecture, Andrei Sakharov spoke of the role played by informed public opinion. He explained:

Freedom of conscience, the existence of an informed public opinion, a system of education of a pluralist nature, freedom of the press, and access to other sources of information… are a vital necessity, not only if all abuse of progress… is to be avoided, but also if we wish to strengthen it… And conversely: intellectual bondage, the power and conformism of a pitiful bureaucracy which from the very start acts as a blight on humanist fields of knowledge, literature, and art, results eventually in a general intellectual decline, bureaucratization and formalization of the entire system of education, a decline of scientific research, and the thwarting of all incentive to creative work, to stagnation, and to dissolution.

With the government having turned decidedly hostile to the press, it is up to the nation’s people to defend its ability to remain unconstrained to perform its vital public information function. In Federalist No. 84, Alexander Hamilton wrote, “I infer, that its security, whatever fine declarations may be inserted in any constitution respecting it, must altogether depend on public opinion, and on the general spirit of the people and of the government.”

Generations from now, the nation’s history books will reveal whether the American people stood with the press—their news media—to enable it to prevail against a movement aimed at stripping it of its independence from the state and its subordination to the will of political leaders. That outcome will have much bearing on the nature of the country in which those future generations reside.